pickle — Object Serialization¶

| Purpose: | Object serialization |

|---|

The pickle module implements an algorithm for turning an

arbitrary Python object into a series of bytes. This process is also

called serializing the object. The byte stream representing the

object can then be transmitted or stored, and later reconstructed to

create a new object with the same characteristics.

Warning

The documentation for pickle makes clear that it offers no

security guarantees. In fact, unpickling data can execute

arbitrary code. Be careful using pickle for inter-process

communication or data storage, and do not trust data that cannot

be verified as secure. See the hmac module for an example

of a secure way to verify the source of a pickled data source.

Encoding and Decoding Data in Strings¶

This first example Uses dumps() to encode a data structure as a

string, then prints the string to the console. It uses a data

structure made up of entirely built-in types. Instances of any class

can be pickled, as will be illustrated in a later example.

import pickle

import pprint

data = [{'a': 'A', 'b': 2, 'c': 3.0}]

print('DATA:', end=' ')

pprint.pprint(data)

data_string = pickle.dumps(data)

print('PICKLE: {!r}'.format(data_string))

By default, the pickle will be written in a binary format most compatible when sharing between Python 3 programs.

$ python3 pickle_string.py

DATA: [{'a': 'A', 'b': 2, 'c': 3.0}]

PICKLE: b'\x80\x03]q\x00}q\x01(X\x01\x00\x00\x00cq\x02G@\x08\x00

\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00X\x01\x00\x00\x00bq\x03K\x02X\x01\x00\x00\x0

0aq\x04X\x01\x00\x00\x00Aq\x05ua.'

After the data is serialized, it can be written to a file, socket, pipe, etc. Later, the file can be read and the data unpickled to construct a new object with the same values.

import pickle

import pprint

data1 = [{'a': 'A', 'b': 2, 'c': 3.0}]

print('BEFORE: ', end=' ')

pprint.pprint(data1)

data1_string = pickle.dumps(data1)

data2 = pickle.loads(data1_string)

print('AFTER : ', end=' ')

pprint.pprint(data2)

print('SAME? :', (data1 is data2))

print('EQUAL?:', (data1 == data2))

The newly constructed object is equal to, but not the same object as, the original.

$ python3 pickle_unpickle.py

BEFORE: [{'a': 'A', 'b': 2, 'c': 3.0}]

AFTER : [{'a': 'A', 'b': 2, 'c': 3.0}]

SAME? : False

EQUAL?: True

Working with Streams¶

In addition to dumps() and loads(), pickle provides

convenience functions for working with file-like streams. It is

possible to write multiple objects to a stream, and then read them

from the stream without knowing in advance how many objects are

written, or how big they are.

import io

import pickle

import pprint

class SimpleObject:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.name_backwards = name[::-1]

return

data = []

data.append(SimpleObject('pickle'))

data.append(SimpleObject('preserve'))

data.append(SimpleObject('last'))

# Simulate a file.

out_s = io.BytesIO()

# Write to the stream

for o in data:

print('WRITING : {} ({})'.format(o.name, o.name_backwards))

pickle.dump(o, out_s)

out_s.flush()

# Set up a read-able stream

in_s = io.BytesIO(out_s.getvalue())

# Read the data

while True:

try:

o = pickle.load(in_s)

except EOFError:

break

else:

print('READ : {} ({})'.format(

o.name, o.name_backwards))

The example simulates streams using two BytesIO buffers. The

first receives the pickled objects, and its value is fed to a second

from which load() reads. A simple database format could use

pickles to store objects, too. The shelve module is one such

implementation.

$ python3 pickle_stream.py

WRITING : pickle (elkcip)

WRITING : preserve (evreserp)

WRITING : last (tsal)

READ : pickle (elkcip)

READ : preserve (evreserp)

READ : last (tsal)

Besides storing data, pickles are handy for inter-process

communication. For example, os.fork() and os.pipe() can be

used to establish worker processes that read job instructions from one

pipe and write the results to another pipe. The core code for managing

the worker pool and sending jobs in and receiving responses can be

reused, since the job and response objects do not have to be based on

a particular class. When using pipes or sockets, do not forget to

flush after dumping each object, to push the data through the

connection to the other end. See the multiprocessing module

for a reusable worker pool manager.

Problems Reconstructing Objects¶

When working with custom classes, the class being pickled must appear in the namespace of the process reading the pickle. Only the data for the instance is pickled, not the class definition. The class name is used to find the constructor to create the new object when unpickling. The following example writes instances of a class to a file.

import pickle

import sys

class SimpleObject:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

l = list(name)

l.reverse()

self.name_backwards = ''.join(l)

if __name__ == '__main__':

data = []

data.append(SimpleObject('pickle'))

data.append(SimpleObject('preserve'))

data.append(SimpleObject('last'))

filename = sys.argv[1]

with open(filename, 'wb') as out_s:

for o in data:

print('WRITING: {} ({})'.format(

o.name, o.name_backwards))

pickle.dump(o, out_s)

When run, the script creates a file based on the name given as argument on the command line.

$ python3 pickle_dump_to_file_1.py test.dat

WRITING: pickle (elkcip)

WRITING: preserve (evreserp)

WRITING: last (tsal)

A simplistic attempt to load the resulting pickled objects fails.

import pickle

import pprint

import sys

filename = sys.argv[1]

with open(filename, 'rb') as in_s:

while True:

try:

o = pickle.load(in_s)

except EOFError:

break

else:

print('READ: {} ({})'.format(

o.name, o.name_backwards))

This version fails because there is no SimpleObject class

available.

$ python3 pickle_load_from_file_1.py test.dat

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "pickle_load_from_file_1.py", line 15, in <module>

o = pickle.load(in_s)

AttributeError: Can't get attribute 'SimpleObject' on <module '_

_main__' from 'pickle_load_from_file_1.py'>

The corrected version, which imports SimpleObject from the

original script, succeeds. Adding this import statement to the end of

the import list allows the script to find the class and construct the

object.

from pickle_dump_to_file_1 import SimpleObject

Running the modified script now produces the desired results.

$ python3 pickle_load_from_file_2.py test.dat

READ: pickle (elkcip)

READ: preserve (evreserp)

READ: last (tsal)

Unpicklable Objects¶

Not all objects can be pickled. Sockets, file handles, database

connections, and other objects with runtime state that depends on the

operating system or another process may not be able to be saved in a

meaningful way. Objects that have non-picklable attributes can define

__getstate__() and __setstate__() to return a subset of the

state of the instance to be pickled.

The __getstate__() method must return an object containing the

internal state of the object. One convenient way to represent that

state is with a dictionary, but the value can be any picklable

object. The state is stored, and passed to __setstate__() when

the object is loaded from the pickle.

import pickle

class State:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def __repr__(self):

return 'State({!r})'.format(self.__dict__)

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, name):

print('MyClass.__init__({})'.format(name))

self._set_name(name)

def _set_name(self, name):

self.name = name

self.computed = name[::-1]

def __repr__(self):

return 'MyClass({!r}) (computed={!r})'.format(

self.name, self.computed)

def __getstate__(self):

state = State(self.name)

print('__getstate__ -> {!r}'.format(state))

return state

def __setstate__(self, state):

print('__setstate__({!r})'.format(state))

self._set_name(state.name)

inst = MyClass('name here')

print('Before:', inst)

dumped = pickle.dumps(inst)

reloaded = pickle.loads(dumped)

print('After:', reloaded)

This example uses a separate State object to hold the

internal state of MyClass. When an instance of

MyClass is loaded from a pickle, __setstate__() is

passed a State instance which it uses to initialize the

object.

$ python3 pickle_state.py

MyClass.__init__(name here)

Before: MyClass('name here') (computed='ereh eman')

__getstate__ -> State({'name': 'name here'})

__setstate__(State({'name': 'name here'}))

After: MyClass('name here') (computed='ereh eman')

Warning

If the return value is false, then __setstate__() is not

called when the object is unpickled.

Circular References¶

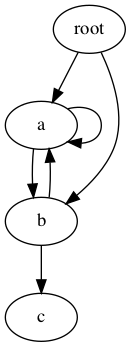

The pickle protocol automatically handles circular references between objects, so complex data structures do not need any special handling. Consider the directed graph in the figure. It includes several cycles, yet the correct structure can be pickled and then reloaded.

Pickling a Data Structure With Cycles¶

import pickle

class Node:

"""A simple digraph

"""

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.connections = []

def add_edge(self, node):

"Create an edge between this node and the other."

self.connections.append(node)

def __iter__(self):

return iter(self.connections)

def preorder_traversal(root, seen=None, parent=None):

"""Generator function to yield the edges in a graph.

"""

if seen is None:

seen = set()

yield (parent, root)

if root in seen:

return

seen.add(root)

for node in root:

recurse = preorder_traversal(node, seen, root)

for parent, subnode in recurse:

yield (parent, subnode)

def show_edges(root):

"Print all the edges in the graph."

for parent, child in preorder_traversal(root):

if not parent:

continue

print('{:>5} -> {:>2} ({})'.format(

parent.name, child.name, id(child)))

# Set up the nodes.

root = Node('root')

a = Node('a')

b = Node('b')

c = Node('c')

# Add edges between them.

root.add_edge(a)

root.add_edge(b)

a.add_edge(b)

b.add_edge(a)

b.add_edge(c)

a.add_edge(a)

print('ORIGINAL GRAPH:')

show_edges(root)

# Pickle and unpickle the graph to create

# a new set of nodes.

dumped = pickle.dumps(root)

reloaded = pickle.loads(dumped)

print('\nRELOADED GRAPH:')

show_edges(reloaded)

The reloaded nodes are not the same object, but the relationship

between the nodes is maintained and only one copy of the object with

multiple references is reloaded. Both of these statements can be

verified by examining the id() values for the nodes before and

after being passed through pickle.

$ python3 pickle_cycle.py

ORIGINAL GRAPH:

root -> a (4315798272)

a -> b (4315798384)

b -> a (4315798272)

b -> c (4315799112)

a -> a (4315798272)

root -> b (4315798384)

RELOADED GRAPH:

root -> a (4315904096)

a -> b (4315904152)

b -> a (4315904096)

b -> c (4315904208)

a -> a (4315904096)

root -> b (4315904152)

See also

- Standard library documentation for pickle

- PEP 3154 – Pickle protocol version 4

shelve– Theshelvemodule usespickleto store data in a DBM database.- Pickle: An interesting stack language. – by Alexandre Vassalotti

PyMOTW-3

PyMOTW-3